In my daily work, I often switch between codebases. Each brings its own ecosystem of tools to create, manage, build and publish source code. One thing to help with the frequent switching is to have a single entry point to work with the source code in every project. I like to have a single wrapper script that allows me to run common commands I need for my daily developer life using consistent conventions, no matter if I’m using Yarn, Cargo, Gradle, Pipenv or a wild combination of tools under the hood.

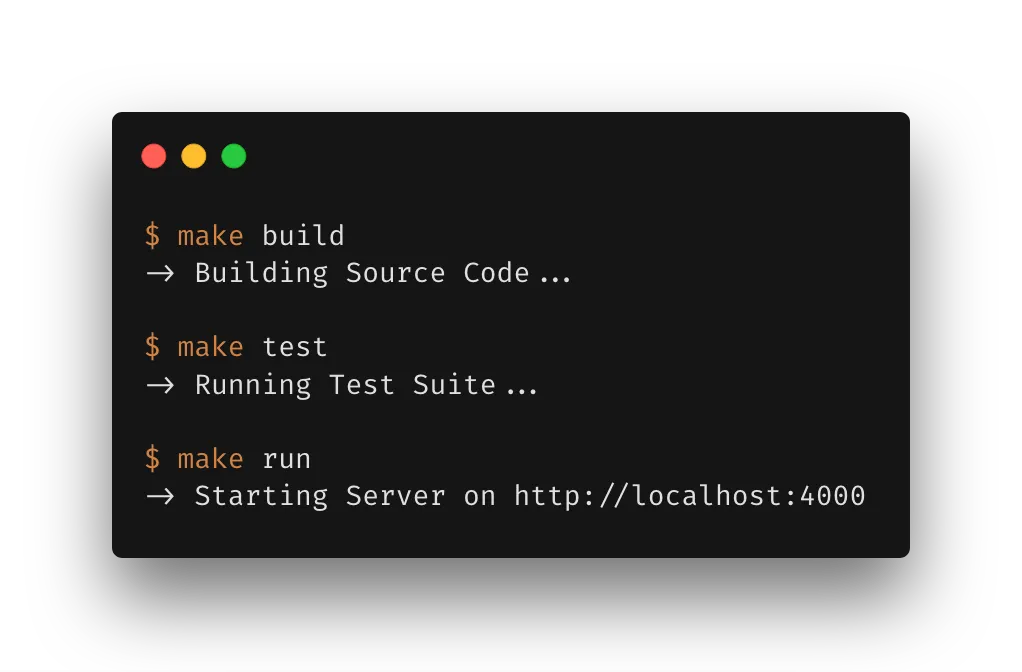

At ThoughtWorks, we often call this a go script (which, admittedly, became confusing after go, the programming language, has become a thing). Teams at ThoughtWorks often create these scripts to make it easy run common tasks automatically: I can call ./go build to compile my source code, ./go test to run the test suite, or ./go run to start the application locally, regardless of the tools that are used under the hood. Pete Hodgson wrote a nice series of articles in praise of the go script to describe this practice in more detail (Part II is here).

Having a script as a single entry point makes your code more accessible to other developers (and your future self!). It’s easy to do the things you want to do without memorizing long-winded commands. It’s easy to switch between different projects as the commands stay mostly the same. And it’s easy to discover what’s possible (by running ./go help) which helps getting new people up to speed.

go Scripts: An Example in Bash

Most of the go scripts I’ve seen were written in bash and roughly followed the same structure of parsing the first parameter and then mapping that to certain actions:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

function usage {

# print usage information

}

function build {

# trigger build process

}

function test {

# run test suite

}

if [[ $# -lt 1 ]]; then

usage

exit 1

fi

TARGET=$1

case $TARGET in

"help" )

usage

;;

"build" )

build

;;

"test" )

test

;;

*)

fail "Unknown command '${TARGET}'"

usage

exit 1

;;

esac

Bash is a natural choice for simple automation tasks like this as it’s often available on developer machines (and your continuous delivery server) and is undeniably powerful.

More recently I discovered that using make can be a better fit for what we’re trying to achieve here. Let’s see how.

make and Makefiles

make itself is more powerful than what we’re using it for here. Usually it’s used for build automation and especially popular in the C/C++ universe for compiling source code but that doesn’t stop it from being useful for other things.

If we want to use make as a simple wrapper to interact with our source code, we don’t need all of its bells and whistles and can start with understanding a few basics:

make looks for a file called Makefile in your current directory to figure out what it’s supposed to do. A Makefile is a plain text file that defines the different rules you can execute.

A rule follows this pattern:

target: dependencies

system command to execute

The target defines how you call the rule from your command line. make initialize-database would look for a rule called “initialize-database” and execute the commands you defined.

An Example Using make

Let’s assume, we have a Python codebase using Flask and want to have a simple way to perform three different actions:

- run unit tests

- start the application locally

- run a code formatter

A corresponding Makefile looks like this:

.PHONY: test run format

test:

pipenv run pytest

run:

export FLASK_ENV=development && \

export FLASK_APP=myapp && \

pipenv run flask run

format:

pipenv run black myapp/

Note Keep in mind that

makeis picky about indentation. You need to indent your commands with a Tab. Copying the above code snippet might not work unless you ensure that you properly indentet your file with tabs, not spaces.

Once we put this Makefile at the root of our project we can simply run make test, make run or make format from our command line to perform the tasks we defined.

.PHONY targets

If you take a close look at the first line of our Makefile you’ll see a line starting with .PHONY::

.PHONY: test run format

This line declares all three of our targets as phony targets, i.e. targets that do not produce or depend on files on our file system. This answer on Stack Overflow does a fantastic job of explaining what this is all about. In a nutshell: make usually expects to create files as output of the targets we run. If these files are in place, make won’t do anything.

As an example:

Take the above Makefile. If we had a file called “format” next to our Makefile and didn’t declare the format target as a phony target, make would lazily refuse to do anything once we run make format. It would just claim:

make: `format' is up to date.

We can’t avoid that someone creates a file with the same name as our make targets. To avoid breaking our make automation, we declare all our targets as phony targets. This way we’re safe from running into the pitfall of having name clashes with files on our file system.

Dependencies

One of the strengths of make is the possibility to declare dependencies between targets. Usually this is meant to work with files on our file system again but we can also use it to chain the rules we have created in our makefile.

Imagine you have a clean target that removes all compiled files from your file system. Occasionally you want to run the clean target by itself but you also want to run it every time before you compile your source code again (because you have way too much time at hand and incremental builds are just not your cup of tea 🤨). In this case you could declare the clean target as a dependency for your build target and make would run clean every time before it runs the build target:

clean:

rm -rf build/

build: clean

# whatever you have to do to build your code

Autocompletion

Another cool gimmick when using make is that some shells provide autocompletion for your targets, either out of the box or by installing a small utility package. zsh and fish support make autocompletion out of the box. If you’re a bash you can get autocompletion - not only for make - by installing this package.

With make autocompletion in place, you can start typing make in your command line and hit tab repeatedly to cycle through the available targets defined in your Makefile.

Caveats

Using make is an easy way to make your project’s source code easy to work with. Make certainly is powerful and that power comes with great responsibility. Makefiles can grow out of hand quickly. Personally, I wouldn’t use make for anything that’s way more complex than what we’ve outlined here. If you just need small wrappers around a certain set of commands, make is a good way to go. It’s available on most systems and your Makefile can be simple and maintainable. As with every tool, you can go overboard easily and produce something that will haunt you for years to come.

Find your sweet spot, and don’t forget what the people collaborating with you feel comfortable with. Just because you’re cool with a big plate of Makefile spaghetti it might not be the best idea to write everything in make. My personal take is that if you need scripts that are more complex than a verb + noun combination (i.e. go deploy production --version=latest instead of make test or go build) you might want to look into something different than make - bash or your scripting language of choice being good options.